Introduction

Every major financial crisis in history—whether the Great Depression, the dot-com bubble, or the 2008 global financial meltdown—has been deeply tied to the expansion and collapse of leverage. When borrowing increases faster than economic output, it fuels growth, investment, and rising asset prices. However, when the tide turns and borrowers are forced to deleverage, the same dynamic leads to asset price crashes, credit shortages, and recessions.

Understanding how leverage cycles shape economic booms and busts is essential for investors, policymakers, and financial institutions. These cycles reveal why markets tend to overheat and why downturns can become so severe.

What Is a Leverage Cycle?

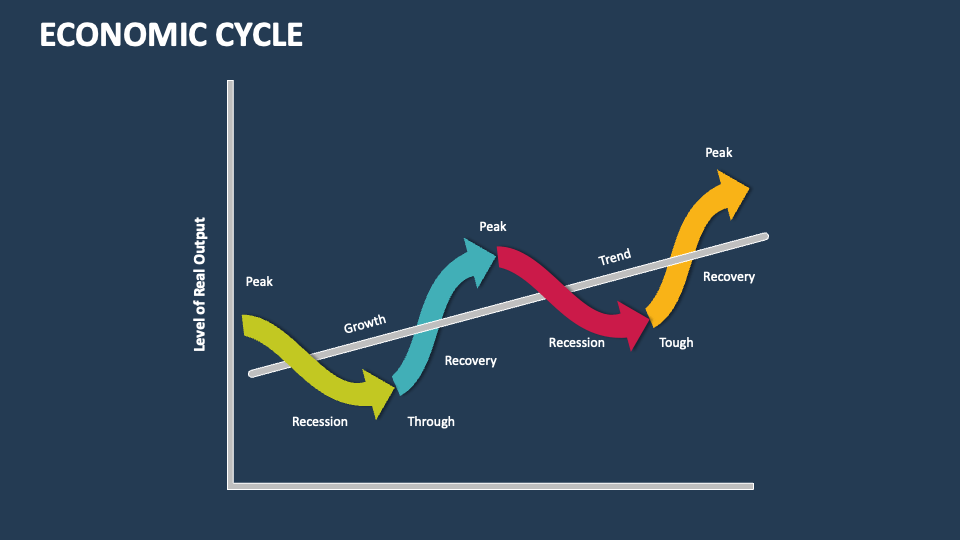

A leverage cycle is a recurring economic pattern characterized by alternating phases of increasing and decreasing leverage in the financial system. In simple terms, it reflects the rhythm of how much debt households, firms, and investors are willing—or able—to take on relative to their income or capital.

During the upswing, optimism dominates. Borrowers and lenders feel confident, risk appetite rises, and credit expands. As more money flows into assets like housing or equities, prices climb, reinforcing the sense of prosperity. In the downswing, fear takes over. Credit contracts, borrowers rush to sell assets to repay debts, and prices fall, often rapidly.

Key Stages of a Leverage Cycle

- Credit Expansion: Lenders loosen credit standards, interest rates remain low, and borrowing increases.

- Asset Price Boom: Rising demand for assets like real estate or stocks drives prices higher, creating paper wealth.

- Overconfidence and Speculation: Investors assume the good times will last, leading to excessive risk-taking.

- Trigger or Shock: A change in interest rates, defaults, or economic slowdown begins to reveal underlying weaknesses.

- Deleveraging: Borrowers repay or default on loans; credit shrinks and asset prices collapse.

- Stabilization and Recovery: After balance sheets are repaired, credit growth resumes, and the next cycle begins.

How Leverage Fuels Economic Booms

During economic expansions, leverage acts as a multiplier. Increased borrowing enables higher spending, investment, and asset accumulation. Companies finance projects through debt, households buy homes or cars on credit, and investors use margin loans to amplify returns.

Mechanisms Driving the Boom

- Low Interest Rates: Central banks often lower rates to stimulate growth. Cheap borrowing encourages risk-taking and credit expansion.

- Rising Asset Values: As asset prices rise, the value of collateral increases, allowing borrowers to take on even more debt.

- Financial Innovation: New financial products—like mortgage-backed securities or derivatives—make borrowing easier and appear safer.

- Optimism and Herd Behavior: Confidence in the economy leads to a collective underestimation of risk, reinforcing the cycle of leverage.

The Wealth Effect

When asset prices rise due to increased borrowing, individuals feel wealthier and spend more, further boosting economic activity. This wealth effect sustains demand but also embeds systemic risk because much of that wealth is leveraged, not real.

How Leverage Triggers Economic Busts

When credit growth slows or reverses, the leverage cycle shifts dramatically. The same forces that fueled growth begin to work in reverse, often with devastating speed and intensity.

The Process of Deleveraging

- Falling Asset Prices: As investors sell assets to cover debts, prices fall, reducing the value of collateral.

- Credit Contraction: Banks and lenders tighten credit standards, restricting new loans.

- Negative Feedback Loop: Declining asset values lead to further deleveraging, worsening the downturn.

- Default and Insolvency: Borrowers unable to repay debts face defaults, bankruptcies, and foreclosures.

The Psychological Shift

In a boom, optimism dominates. In a bust, fear takes over. Investors who once believed risk was minimal suddenly become risk-averse. This collective shift in sentiment accelerates deleveraging and deepens recessions.

The Role of Banks and Financial Institutions

Banks and financial intermediaries play a central role in the leverage cycle. Their lending decisions directly influence credit availability, liquidity, and asset prices.

How Banks Amplify the Cycle

- During Booms: Banks expand lending aggressively, using rising asset values as justification for more credit.

- During Busts: The same institutions withdraw credit to protect themselves, worsening liquidity shortages.

- Procyclicality: This tendency to lend more during expansions and less during contractions makes banks powerful amplifiers of economic cycles.

The Shadow Banking System

Beyond traditional banks, the shadow banking sector—including hedge funds, private equity firms, and money market funds—adds complexity to leverage cycles. These institutions are often lightly regulated and rely heavily on short-term funding, making them vulnerable to rapid reversals in liquidity.

Indicators of a Leverage Cycle

To identify where the economy stands in the leverage cycle, analysts and policymakers monitor several key indicators:

- Debt-to-GDP Ratio: Measures total debt relative to economic output.

- Household and Corporate Leverage: High ratios indicate rising systemic risk.

- Credit Growth Rate: Rapid credit expansion is often a precursor to bubbles.

- Asset Price Inflation: Unusual surges in real estate or equity prices suggest excessive leverage.

- Bank Lending Standards: When banks ease lending criteria, it may signal late-stage credit expansion.

Historical Examples of Leverage Cycles

The Great Depression (1929–1939)

Excessive margin borrowing fueled the 1920s stock market boom. When prices collapsed, leveraged investors were forced to sell, intensifying the crash and leading to a decade-long economic depression.

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis

In the early 2000s, easy credit and financial engineering led to unprecedented levels of mortgage leverage. When housing prices fell, the entire global banking system faced collapse due to interconnected leverage exposures.

Japan’s Asset Bubble (1980s–1990s)

Japan experienced massive real estate and stock market inflation driven by credit growth. When the bubble burst, Japan entered a prolonged period of stagnation known as the “Lost Decade.”

Policy Responses to Leverage Cycles

Policymakers have developed tools to moderate leverage cycles and prevent severe booms and busts.

Monetary Policy

Central banks can influence borrowing through interest rates and liquidity measures. Raising rates can curb excessive leverage, while lowering them supports recovery during deleveraging phases.

Macroprudential Regulation

Authorities use capital requirements, loan-to-value (LTV) ratios, and stress testing to ensure that financial institutions remain resilient during downturns.

Fiscal Policy

Governments may counteract private-sector deleveraging through public spending or tax relief, stabilizing demand during recessions.

How Investors and Businesses Can Manage Leverage Risk

- Diversify Assets: Avoid overexposure to leveraged sectors or instruments.

- Monitor Debt Ratios: Both corporate and personal balance sheets should maintain sustainable leverage levels.

- Maintain Liquidity Buffers: Access to cash during downturns prevents forced asset sales.

- Stay Vigilant on Market Sentiment: Overconfidence often precedes downturns. Recognizing euphoric conditions can protect capital.

- Use Counter-Cyclical Strategies: Increase savings and reduce debt during booms to prepare for eventual downturns.

The Future of Leverage Cycles

As financial systems become more complex, leverage cycles are evolving. Innovations in decentralized finance (DeFi), private credit, and global capital flows create new sources of leverage outside traditional banking. These may bring efficiency but also new vulnerabilities. Understanding leverage will remain critical for maintaining financial stability in the decades ahead.

Conclusion

Leverage cycles are the heartbeat of modern economies—alternating between optimism and fear, expansion and contraction. While they cannot be eliminated, they can be managed. Recognizing their patterns helps policymakers reduce volatility, investors make wiser decisions, and societies prepare for inevitable downturns. The challenge is not to avoid leverage altogether but to balance ambition with prudence, ensuring growth without risking collapse.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the main difference between leverage and debt?

Leverage is the use of debt to amplify returns on investment, while debt itself is simply borrowed money. All leverage involves debt, but not all debt is leveraged.

2. How do central banks influence leverage cycles?

Central banks affect leverage through interest rate adjustments and liquidity policies. Low rates encourage borrowing, while higher rates discourage it.

3. Can leverage cycles be predicted accurately?

While no model can predict cycles perfectly, early warning indicators—such as rapid credit growth or surging asset prices—often signal excessive leverage buildup.

4. Why do investors continue to take excessive risks despite past crises?

Human behavior tends to discount past risks during good times. Optimism, herd behavior, and short-term incentives encourage over-borrowing and speculation.

5. Are leverage cycles the same across countries?

No. Leverage cycles differ depending on regulatory structures, financial culture, and monetary policy. However, their core mechanics are similar globally.

6. How can individuals protect themselves during a deleveraging phase?

Reducing debt, maintaining cash reserves, and diversifying investments are key strategies to weather downturns caused by deleveraging.

7. What lessons can policymakers learn from past leverage cycles?

The main lesson is that preventing excessive credit booms through prudent regulation and transparency is far less costly than managing their aftermath.